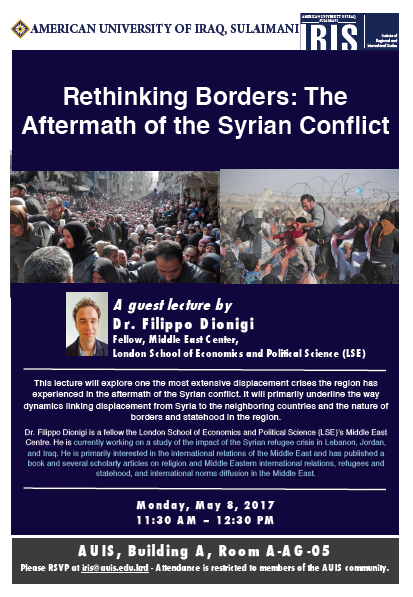

On May 8, 2017, IRIS hosted a guest lecture , titlted "Rethinking Borders: The Aftermath of the Syrian Conflict," by Dr. Filippo Dionigi, a fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE)’s Middle East Centre, currently working on a study of the impact of the Syrian refugee crisis in Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq.

He opened his talk with a presentation of the concept of “border thinness” as it applies to Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq and its Kurdistan Region (KRI). His central argument was that the current displacement crisis has been facilitated by border thinness, which allows for fast and intense population movements.

The concept of border thinness, he continued, is one drawn from architecture. Borders are much more complex than mere lines on the ground. Four main layers, or boundaries, were used by Dionigi to define borders and assess border thinness (or thickness): (1) the political boundary, or the regulatory framework highlighting power dynamics; (2) the cultural or social boundary; (3) the economic boundary, or the integration of economic transactions; and (4) the physical boundary.

Using this framework, he moved to an analysis of Syria’s borders with Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq, arguing that in most cases, all four boundaries had been challenged historically, making for very thin borders. Drawing insight from political alliances and fallouts in modern history, he argued that political contexts in the region had been very vulnerable to neighbors’ influences. Culturally and socially, many ethno-religious linkages also exist between Shi’a, Sunni, and Kurdish communities. Family ties can also be observed, as in the case of areas of Daraa (Syria) and Mafraq (Jordan), which share very close tribal bonds. The example of Syrian Rojava and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq also highlights the importance of cultural ties in facilitating population movements. Economic boundaries are also very thin, Dionigi claimed. From free trade agreements to close integration of financial service sectors, Syria has, before the crisis, had strong economic relations with most of its neighbors, with the exception of Israel. The Syrian-Israeli border, Dionigi in fact claimed, is a prime example of border thickness. Finally, physical boundaries have also been challenged. Many present difficult terrain (mountains, desert), which has made patrolling problematic, thereby allowing a more intense population flow.

In the context of a humanitarian crisis, Dionigi concluded, border thinness has several implications. First, it represents an opportunity for political and social/humanitarian actors to project power across borders and directly intervene in conflict. Second, preexisting knowledge and social networks provide incentive for displacement, rendering the decision to flee “easier.” Conversely, border thinness also helps political leaders justify the presence of refugees on their land, as is the case in the KRI, where politicians use the expression “Kurdish brothers” to refer to Syrian refugees.

A podcast will be available soon.