What is IIR?

The IRIS Iraq Report (IIR) offers on-the-ground reporting and analysis on Iraq’s most pressing issues. It is aimed at providing decision-makers and experts with solid research and analysis of Iraq policy. The Report is unique because it is produced in Iraq, and is based on in-country fieldwork as well as open source research. It is the brainchild of Ahmed Ali and Christine van den Toorn, both of whom have years of experience researching and writing on Iraq and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

Summary

One success story in the war against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) happened in October 2014, when Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga cooperated with the Iraqi Shammar tribe to clear ISIS from the predominantly Sunni Arab border town of Rabia in northern Iraq’s Ninewa province. This military alliance was essential to defeating ISIS and denying it control of contiguous terrain between Iraq and Syria. It is a positive example of former rivals setting aside their differences in order to neutralize ISIS. The security gains in Rabia were complemented by the return of the large majority of the local population who fled when ISIS attacked.

However, the road ahead is more difficult than the one behind. The current Iraqi Kurdish-Iraqi Sunni Arab alliance is in jeopardy for a multitude of reasons. Strategically, local and national stakeholders cannot define the final status of Rabia as part of either federal Iraq or Iraqi Kurdistan. On the ground, dormant ethnic tensions, intra-tribal power struggles, mistrust, territorial disputes, and lack of reconstruction in the area will challenge the pact.

Success in Rabia is crucial in order to inspire similar military alliances in other predominantly Sunni parts of Iraq like Mosul, Anbar and Salahddin. Furthermore, it will prevent ISIS from regaining a presence on the Iraqi-Syrian border. Therefore, Baghdad, Erbil, local tribes, and the United States have an imperative interest in achieving a positive outcome in Rabia.

Background: ISIS attacks Rabia

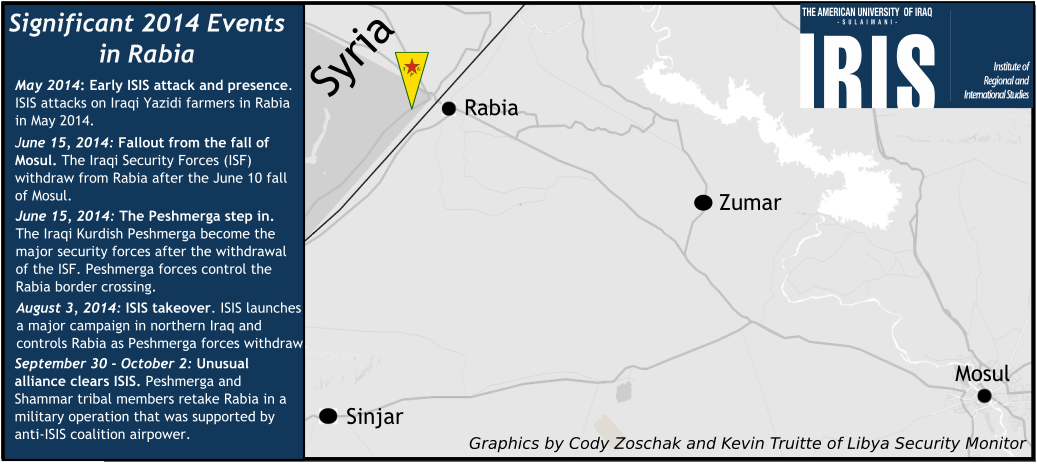

In August 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) took control of Rabia -- a strategic sub-district, or nahiya, in Ninewa province on the border with Syria -- and its surrounding areas, Zumar, and most infamously the Yazidi district of Sinjar, which lies just south. Rabia is dominated by the Iraqi Arab tribe of Shammar, one of Iraq’s biggest tribal confederations or qabila. ISIS had taken control of neighboring Mosul and Tal Afar, the district, or qadha, to which it belongs, located east and southeast of Rabia, earlier in the summer.

The conquest of Rabia, Sinjar and Zumar solidified ISIS’ hold on Ninewa and prompted them to move further east toward Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, reaching the Makhmour area. Those events prompted the anti-ISIS coalition air campaign.

ISIS had a presence and freedom of movement in Rabia by May 2014 despite the presence of the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF). During that period, it attacked Iraqi Yazidis working in Rabia’s farms and fleeing Sinjar through Rabia in anticipation of an ISIS assault. ISIS bombed the homes of Shammar sheikhs who were allied with the Iraqi state and attacked Rabia-based Peshmerga through June and July of 2014 to soften Peshmerga defenses in areas west of Mosul.

Control of Rabia was significant for the Iraqi government and the United States military in the aftermath of the 2003 fall of Saddam Hussein. For ISIS, control of Rabia was important in order for the group to maintain contiguous control of terrain in northwestern Iraq and between Iraq and Syria. The sub-district is in a strategic position between Mosul and Syria, borders Sinjar and is part of Tal Afar, all areas ISIS conquered. It includes a border crossing that, traditionally, along with the surrounding areas, has acted as a lucrative business center for local tribes and multiple Iraqi governments. Rabia is well-known for its fertile soil and agriculture, from which ISIS could also benefit. It was also a message that Sunni Arabs who resisted the group would face severe consequences.

In October 2014, Rabia was liberated in a relatively quick operation because of the joint Sunni Arab Shammar-Peshmerga alliance that attacked under cover of coalition air support. Tactically, members of the Shammar tribe acted as guides for the Peshmerga during the operation and directed them to ISIS positions and areas where ISIS had implanted Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs). A second key component in the swift liberation was the fact that most Shammar, the majority tribe in the area, and one of the largest in Iraq, did not collaborate with ISIS.

Shammar-KDP Alliance

The joint Shammar-Peshmerga force that liberated Rabia was made possible by a deal between Sheikh Abdullah Ajil al-Yawer, a prominent Shammar Sheikh in Rabia, and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the leading Kurdish party in Ninewa and Dohuk, a province of Iraqi Kurdistan that borders Rabia. Al-Yawer has since then stated to multiple outlets that the Shammar and Peshmerga were in “full cooperation.” He makes regular visits to Erbil and his good relations with various senior KDP leaders.

Such deals between Sunni Arabs and Kurds are nothing new. For instance, the former governor of Ninewa, Atheel al-Nujaifi, who was in office from 2009 to 2015, was a vocal critic of Iraqi Kurdish policies and presence in Ninewa. However, by late 2012 he shifted his position and became an ally of the KDP as his relations with Baghdad worsened. This was motivated by oil deals between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and international oil companies in areas that are officially part of Ninewa such as Bashiqa and Qaraqosh. Nujaifi’s brother, Osama, who was the speaker of Iraq’s Council of Representatives (CoR), also shifted his position from anti-Iraqi Kurdish to what is currently a complete alliance.

For the Shammar, the alliance falls within the long-established tribal policy of building relations with the dominant adjacent power. Traditionally, tribal policy is based on survival and pragmatism. These realities and the threat of ISIS made the Shammar alliance with Peshmerga more possible. As al-Yawer told the authors, “I will do whatever it takes to allow my people to go back.” This situation and desire are present in multiple predominantly Iraqi Sunni areas. Baghdad and the KRG must capitalize on these conditions to facilitate the clearing of ISIS.

However, in ways the deal is a shift from past Shammar policy toward the Kurds. Relations between KDP and al-Yawer, and other Shammar sheikhs, have been tense at times over the past ten years. Since the 2003 fall of Saddam Hussein, Iraqi Sunni leaders including the Shammar possess perceived and real grievances towards the more powerful Iraqi Shi’a and Kurdish parties. In Ninewa it has been the rise of Kurdish influence, and Shammar claim the KDP has taken steps to marginalize their political, economic and social power around Rabia and the greater province. The KDP, on the other hand, state they have and are ready to continue to contribute to development in Rabia.

Potentially the biggest threat to the alliance is that branches and personalities within the Shammar tribe, both sheikhs and tribesmen, are steadfast in their opposition to any deal with the KDP and the Kurds, and seek to work with Baghdad to secure the future of Rabia. So while the dominating presence of one tribe in Rabia facilitates any future political deals and security arrangements, like most tribes in Iraq the Shammar are not united politically or socially.

Rabia post-ISIS

The picture in Rabia is mixed. One of the successes in the area is its repopulation. Of the area’s 13,000 families, 12,000 have returned. Realistically, it is easier to repopulate Rabia given the fact that the majority of the population did not support ISIS. Furthermore, it is easier to vet families in Rabia because of its uniform tribal landscape, which allows for a system of future accountability. Most of these families were based in Dohuk and across the border in Syria.

Security in the area is stable as the Peshmerga forces are stationed around the sub-district with locals providing security inside the city. Last fall, Zerevani Peshmerga – Iraqi Kurdistan’s militarized police force – trained 200 Shammar tribal members, and in August 2015 the Peshmerga provided 100 AK 47 machine guns to Shammar tribal members. The Syrian Kurdish Yekineyen Parastina Gel (YPG), which has close ties with the PKK in neighboring Turkey, controls the Yarubiyah border crossing on the Syrian side. As a result, ISIS has not been able to represent a threat to Rabia since October 2014. Additionally, ISIS has been unable to launch attacks probably because of its plan to protect its positions in Tal Afar to the east and Sinjar to the south of Rabia.

In contrast to the security situation, the infrastructure and services in Rabia are still depleted almost a year after its clearing. There is a lack of electricity and water provision. There are also complaints about school conditions and shortages of teachers. Neither Baghdad nor Erbil has provided Rabia with services. This is partially because of the ongoing anti-ISIS war and the country’s economic crisis. It is also an example of classic disputed territory politics. The federal government views Rabia skeptically for building alliances with Erbil and in return the KRG is unable or unwilling to fully commit to a territory outside the constitutionally-defined Iraqi Kurdistan. To be sure, Rabia has been under-resourced for a long period of time. However, given that it has set a good example in post-ISIS repopulation, better service delivery could serve as a model for other tribes in Iraq to turn against ISIS. The lack of rebuilding in Rabia sends a discouraging message to the rest of Iraq as it grapples with a post-ISIS future.

Conclusions

Clearing ISIS through Peshmerga-tribal cooperation is a positive model, and a military combination that can be replicated elsewhere in Iraq. The success of the model will depend on the backing of coalition air power and participation of local security forces. The situation in Rabia demonstrates that rivals can, at least temporarily, put differences aside and overcome their past tensions to defeat ISIS. This modus operandi can be applied to relations between Baghdad and Iraqi Sunni tribes. That said, tribes in other areas are not as clear-cut as the Shammar are with regard to ISIS. Elsewhere in Iraq, tribes are split, with sections supporting ISIS and others opposing it. This difference complicates Baghdad’s approach to the Iraqi Sunni tribes that are perceived as having partly supported ISIS. Militarily, Rabia should be considered as a launching pad for future operations to clear ISIS in Tal Afar, Sinjar, and Mosul.

Moving forward, different scenarios for the security structure in Rabia will exist. The first possibility is the return of the pre-ISIS security architecture composed of Iraqi federal government forces. Before the August ISIS takeover of Rabia, it was under the control of the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) and Iraqi Border Police (IBP). The Shammar in the area were prominent in the security infrastructure as most of them were in the local Iraqi Police (IP). Peshmerga will also likely be in the area. Iraqi Kurdish forces are currently positioned to the east of the center of Rabia in the town of Zumar, which is important for the Iraqi Kurds as it falls within what is known as the Disputed Internal Boundaries (DIBs) areas and has untapped oil reserves. DIBs areas are disputed between Baghdad and Erbil and are supposed to be solved according to article 140 of the Iraqi constitution.

Due to the withdrawal of both ISF and then Peshmerga from the area in the summer of 2014, it is certain that there will be a major local component to any new force. Local Shammar forces are already in place and currently fall under the Ministry of Peshmerga. Nevertheless, their affiliation could shift to the Ministry of Defense or Ministry of Interior in Baghdad, depending on disputed territory deals. In either case, conditions in the area can improve as long as the Shammar cooperate with the Peshmerga or ISF and vice versa. Power struggles between Baghdad and Erbil could exacerbate intra-Shammar disagreements and will jeopardize stability in Rabia.

The YPG can play a role in maintaining security in the area by ensuring stability across the border. Thus far, there have not been any cross-border issues. The YPG will have to maintain a neutral stance and cannot be involved in the politics of the area. Its role will be more positive if it remains strictly focused on security.

From a governance standpoint, the future of Rabia is still uncertain. Sheikh Abdullah al-Yawer told the authors, “We do not know the endgame.” The success of the current situation will depend on multiple national and local actors. For now, the deal between the KDP and the Shammar is hyper local and isolated from national politics. It is based on the assumption that the cooperative relations between both sides will continue. It further assumes that Baghdad will continue to be preoccupied with other parts of the country and disregard the significance of Rabia. These two conditions are fluid.

To avoid regression in the deal between the KDP and the Shammar, both sides will have to maintain the current alliance based on power sharing. If the Shammar and the Kurds are unable to do so – a possibility considering the shifting alliances in Iraq – there could be major security and governance gaps that ISIS, or some future reincarnation of ISIS, will exploit in order to establish a foothold in the area. Indeed, ISIS is adept at exploiting ethno-sectarian tensions. Local and national actors must avoid a return to status quo political and social dynamics that existed before and facilitated the rise of ISIS.Thus, the KDP-Shammar alliance will need to be monitored by the United States, particularly in the very likely event of Baghdad’s involvement in the area.

The Shammar-KDP alliance is an example of political deals in a post-ISIS world: one between former foes motivated by mutual interest, political competition and a shared anti-ISIS outlook. This instance stands out, but is not the only time Iraqi Kurds and Iraqi Arabs have cooperated against ISIS: joint efforts between Iraqi Arab Shi’a and Iraqi Kurds in Diyala and Salahddin province are another example. Former enemies can certainly become allies.

Locally, the deal between the Shammar and the KDP can also collapse in the future. Active competition between them as well as intra-Shammar division and opposition is possible as the ISIS threat that unites them subsides. As one prominent Shammar Sheikh told the authors, “There should not be airpower from above if there is no political deal on the ground.” To him, the deal with the KDP was personal and not representative of the entire Shammar tribe. In order for the deal to be sustainable, al-Yawer will have to show it yields concrete results and benefits for the people. This means the KDP and KRG will have to contribute to reconstruction in Rabia.

Another issue will be the administration and changing ethno sectarian demographics related to Tal Afar and the creation of new provinces. After ISIS is cleared from Mosul, there will undoubtedly be an initiative to establish Tal Afar as a province. Presumably, this will include Rabia, which legally belongs to what is the district of Tal Afar. Tal Afar was a mixed Iraqi Shi’a and Sunni Turkmen town that is now an epicenter -- if not the epicenter -- of ISIS activity. If and when it is cleared it could be a majority Shia Turkmen province. Inclusion in such an area will be resisted by both the KRG and local Shammar tribe, who are already advocating for the establishment of Rabia as a separate province. The U.S. is trusted by all parties in Rabia given its previous work with al-Yawer and established relations with Baghdad and Erbil. Therefore, an active American role in this regard as well will be significant to mediate future tensions.

The local demands for the province of Rabia will likely get traction moving forward. One impetus for establishing the province will be the result of the security breakdown that took place between June and August 2014, culminating in ISIS taking control of Rabia. The demands will also be motivated by the lack of development in Rabia over the last ten years. Such demands for local autonomy, which exist in multiple provinces in Iraq today, will have to be balanced with the central state – be that in Baghdad or Erbil.

There will also need to be a sincere reconciliation process with the neighboring Yezidis of Sinjar. This is possible due to the historic socio-economic relations between the two groups, and the fact the Shammar did not align with ISIS. While unique, it can serve as a starting point and model for ethno sectarian reconciliation in Iraq.

Questions about the administrative status of Rabia reflect the patchwork of actors that have been involved in the area and can complicate an already tenuous situation. Before the 2014 ISIS campaign, Rabia was not technically part of the Disputed Internal Boundaries (DIBs) areas. However, Peshmerga fought and died to clear the area and therefore the KRG perceives that it has a right in determining its future. Geographically, Rabia lies between Sinjar - a major region in the DIBs discussion - and Dohuk. But Rabia is strategic for Baghdad as it borders the non-DIBs territories of Mosul and Tal Afar. Additionally, it contains a border crossing that Baghdad will see as key for its territorial integrity and the huge financial gain from tariffs. Local determinism will be a factor, and Baghdad will unlikely cede Rabia de facto. It will rather be subject to the future agreements that will eventually settle the DIBs and new borders as well as areas of control in a post-ISIS Iraq. In this sense, Rabia is an example of the new territorial challenges that Iraq faces in the aftermath of clearing ISIS. Such areas remain in a transitional phase of ongoing local power struggles which should be watched closely by parties with an interest in stabilization.

To download the full inaugural IRIS Iraq Report (IIR), please click here.